Games have brought us joy for millennia and even digital games have fifty odd years of history behind them. Digital gaming first exploded in the 1980s, as game consoles and cheap home computers began to appear in our homes and everyday lives. The first generations to grow up with digital games are now middle-aged and they haven’t necessarily given up gaming.

According to the University of Tampere’s Player Barometer, around 65% of Finns play digital games at least once a month. When other forms of gaming are included, 89% of the population are active players. Almost all young people play digital games at least sometimes. Only 3.4% of those aged 10 to 19 and 7.1% of those aged 20 to 29 never play digital games. Gaming is a phenomenon that extends throughout the nation and our society, particularly amongst younger people. Games are one of the most popular forms of art and culture.

As well as playing games, here in Finland we also make a lot of games. The commercial production of digital games currently employs round 4000 individuals in a few hundred firms. The sector has a domestic turnover in the region of 3 billion euros. These figures attract significant media coverage, which in turn feeds interest in the topic. People are interested in game development. It can also be a hobby.

On games and making them

In the modern world, games encompass a wide array of different products and pursuits. This article focuses on digital games such as those played on computers, game consoles and mobile devices. As anyone who has ever played Monopoly or poker knows, of course, digital games represent just a fraction of the games that are out there. Beyond traditional boardgames and card games, there are also other physical – or ‘analogue’ – tabletop games, including tabletop miniature games. Assembling and painting the figures and terrain for these games is itself a rather popular pastime.

Leaning towards the verbal arts, tabletop role-playing games are in a class of their own. This is collaborative storytelling in which players work together to tell the story of their own player character, with a gamemaster ensuring that play follows the natural law and story arcs of the game world. In live action role-play games (or LARPs), players, dressed and kitted out as their characters, are fully immersed in the world created by the game arrangers. LARPs are related to improv theatre in their “embodiedness” but, unlike improv, they are not performed for an audience. All participants are part of the game.

Yard games, sports, playable art installations, choose-your-own-adventure books…whole books could be devoted to the different ways of playing. Games are further categorised into different genres. Broadly speaking, games can be classified as either action games, requiring coordination and quick decision-making or strategy games which are slower and incorporate longer cause-effect relationships. Typical action genres include shooter games, racing games and platform games (also known as “jump n’ run” games). Strategic genres include role-playing games, world conquest strategy games and puzzle-solving games that require calm reasoning. These genres can all be further classified in to ever smaller and more specific subgenres.

In a 2012 article, I identified around 50 different genres in use in different sources. Of these, the majority described the function of the game, with labels such as racing game or shooter game. Other labels were associated with the theme of the game. Horror and sports are examples of thematic genres. At the time, I identified a total of 13 overarching genres. Now, 10 years on, the range of genres is broader than ever and there are likely hundreds of genres in play.

There are various roles involved in creating a game. Typically, a game needs a designer – someone who can draw together the ideas into a coherent whole that corresponds with the motivation and skill development of players. Story development and world-building also fall under the remit of the game designer, alongside many other tasks. Both digital and physical games involve visual design. The work of a graphic designer is extremely broad, from visualising user interfaces to animating 3D characters. Digital games also tend to incorporate sound design and music, with these falling to a composer or sound engineer. The logic and functionality of the game world is, naturally, accomplished through programming. There are countless highly specialised areas in game coding, including systems programming, multi-player server coding and game logic. Beyond the central game development roles, the team will usually also include a producer who ensures the production remains within budget and on schedule and that team members have all the resources they need.

The various game development roles are rarely shared out evenly within the team. At times, a single person might do everything, but usually various people are needed for each of the different tasks. Large game development projects might involve hundreds of people, with some concentrating on specific areas in great detail and others operating as higher-level architects, head designers and team leaders.

Easy and fun?

“Making a game is easy. Making a good game is hard. Making a successful game is impossible”- there’s a kernel of truth in this quote by game researcher Annakaisa Kultima. Creating a simple digital game takes a matter of hours. Making a game capable of impressing more than yourself, your friends and relatives, however, requires skill, motivation and opportunity. Even this doesn’t guarantee success; success requires perseverance, capital and a good dose of luck.

In recreational game development, there’s no need to aim for success or a career in game design. Alongside commercial entertainment products, games can be art – a medium for the maker to express something about their lives, to draw attention to social issues and explore the human condition. Games can also be just a bit of fun you come up with to amuse your friends. In the past, we made home videos and played punk music. Nowadays, young people are increasingly expressing themselves through the medium of games.

Games possess the same expressive and communicative power as other forms of art. Gaming influences how we see the world and how we process information and experiences in the same way as other hobbies such as scouts or ice-hockey (also a game) or taking care of horses. Game-making has joined the ranks of other pastimes such as playing in a band, taking art classes, writing poetry and amateur dramatics, and thousands of Finns already practise it. People mostly design games solo or with friends, but more a formal, organised approach to the hobby is already gaining a foothold.

Let’s jam

One of the easiest and most enjoyable ways to get into game design is to participate in a game jam. These events are typically held over a weekend. Participants are assigned a theme on Friday evening and have until Sunday evening to create a game based around that theme. Participants can participate individually or with a group of friends. It can also be highly rewarding to assemble a team of strangers to work closely with over the weekend. Game jams are not about identifying solutions to a particular problem, nor do they offer mentoring or the opportunity to spar with others. Rather, participants figure out answers to the challenges they set themselves. Food and drink, however, are often on offer, typically sponsored by a local game firm.

In addition to weekend game jams in specific locations, jams can also be organised remotely online or at a slower pace. Ludum Dare is one example. This internet jam has been going for years and has been held over 50 times. Makers participate from their own workstations over the space of a weekend. In slow jams, makers might be given a month or two to develop their ideas with the groups working together, say, one day a week. In between sessions, participants may continue to think about and develop the game. There are similarities between this kind of event and a game development club, but both the time limit and the goal of creating a playable game lend structure and direction to the activity. The idea of developing the game in your own time and with your resources also distinguishes slow jams from game development clubs.

Jams in Finland are rarely competitive. In contrast with many other countries, jams here emphasise free expression and experimentation. In a game jam, it doesn’t matter if the game doesn’t really work or if the graphics are a bit rough. The most important thing is trying something, experimenting and having fun. Jams also attract game industry professionals and serious hobbyists, so first-timers may well have the chance to observe veteran developers at work.

The biggest event of the year, the Finnish Game Jam (FGJ), is held in late January, early February each year. Around a thousand game makers assemble in 10 different locations around the country. The Finnish Game Jam is part of the Global Game Jam, an international event organised the same weekend and with the same themes and tasks as FGJ. Smaller game jams are organised in different firms and educational institutions in connection with the online game event Assembly. More information on game jams can be found on the Finnish Game Jam website (https://www.finnishgamejam.com).

Game dev clubs

Clubs also offer a forum for game development in numerous cities around Finland. In some municipalities, programmes are arranged by schools as an extra-curricular activity. Game development activities may also be organised by a municipality’s youth services. There is nothing stopping parishes, adult education centres or art schools from providing sessions in game art design. The main thing is to ensure that there is a knowledgeable session leader, appropriate devices, time and a workspace.

A capable session leader – a student or game industry professional – will be able to guide participants through the various stages of the game development process. They should be able to analyse games and ideas and offer ideas for improvement. An experienced game designer will be able to assess how big and complicated a given project will likely turn out to be and whether it is even worth attempting. Participants who have only ever played massive games may not necessarily have a good sense of what is “enough” when it comes to game design. Trying to recreate League of Legends, Rocket League or even Among Us on your first attempt is more than likely futile. Your first game should be a project you can complete quickly or, at very least, a project you can complete.

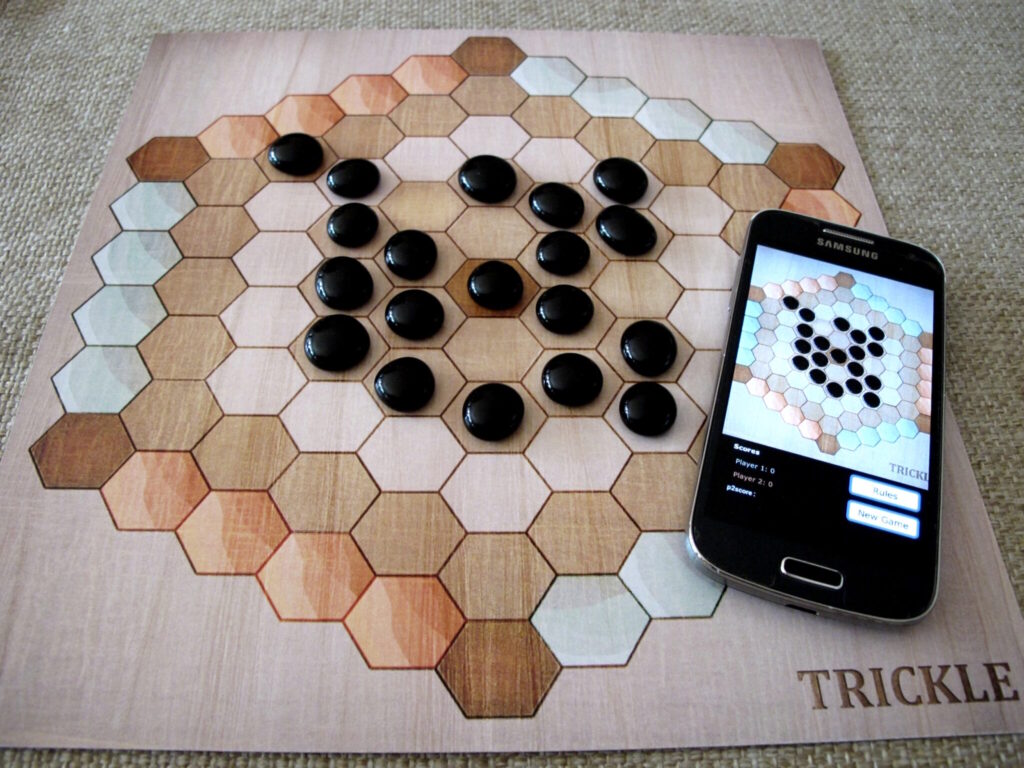

If participants are interested, it pays to begin with board games. Here you can quickly see the results of your handiwork and can trial the game mechanics and the rules in rapid cycles. The easiest way to start is to take an existing game and begin modifying the rules one-by-one. This approach transformed Finnish boardgame Afrikan Tähti [The Star of Africa] into a pirate adventure played on randomly generated navigation charts. Boardgames are not a separate endeavour from digital games. Many digital game creators also dabble in boardgame design, and, conversely, when designing digital games, will first create boardgame-style paper prototypes that enable them to test out specific elements of the actual game more quickly and with fewer resources than programming for real.

In both digital games and boardgames it is important to dive straight in and try out a rough draft of the graphics, sounds, code and rules to test whether the makers’ ideas are even feasible. There is nothing more disheartening than getting excellent 3D models publication-ready, only to find out that the mechanics of the game need to be changed and your models scrapped. An experienced session leader can assist participants in allocating their resources and help them avoid major frustrations.

Camps

Game development camps are somewhere between a club and a jam. Participants come together in a single location for a weekend or even longer and create games under the guidance of an organiser. Camps adopt the time limit and team format of the game jam and the experienced leader and thematic freedom of game development clubs. In a camp, participants stay onsite. Organisers may be responsible for providing food or the whole group may cook together.

Leading a game development club and organising a game development camp both require an understanding of how games work. It’s not just about using software or being able to program. You also need to be familiar with graphics tools and audio technologies and the game engine that’s being used. Game design is a profession in its own right, encompassing everything from devising rules and writing stories to understanding player psychology and game balance. Balancing a game – making it fairer – might involve nerfing, when you decrease the power of an item, character or skill within the game, or conversely, buffing, when these elements are strengthened.

Commercial games today are a far cry from classics such as Monopoly and The Star of Africa. In today’s market, Monopoly would not make it through to release; the game is not well balanced, and the winner is clear long before the game ends. For many contemporary game publishers, the roll-to-move mechanism used in The Star of Africa would mean an automatic rejection. Both these games are fun – especially for children and beginners – and relatively easy to copy, but they are not particularly good games by modern standards.

When planning game development events, it pays to try and bring experienced game designers on board to help plan and direct the activities and offer feedback. The advice, comments and stories of an experienced professional can offer participants an interesting look behind the scenes of the game world and may even encourage them to study or pursue a career in the industry.

Self-directed work

The majority of games are still made by hobbyists in their own time, through a process of trial and error and watching online video tutorials. Finland has traditionally had a very strong hobby culture and several notable success stories have grown out of hobby projects in the field. As previously noted, those who have always played big games often have quite unrealistic expectations of the skills necessary and the work involved. A mentor is helpful here, someone who can help break down the process into manageable steps.

Industry professionals can be invited to visit clubs, libraries and youth centres to talk about making games and point young people towards further resources.

There are few, if any, up-to-date written resources for beginners in Finnish, nor do people tend to read much these days. Online videos can be helpful, especially if you fancy trying your hand at block coding in Minecraft or Roblox. Designed for children, the Scratch programming environment is an accessible program for building two-dimensional games. Scratch teaches the basics of programming and comes with a wealth of instructional resources, both text and video. As your skills improve, you will generally require better tools and the Unity game engine fits the bill. Employed by professionals, Unity can be used to create proper commercial games. While the engine does require some understanding of game logic, 3D mathematics and game development, it offers hobbyists an easier entry point than traditional hard coding.

Ideally, hobbyists would be able to find each other and work together, each in a role that suits their interests. Beyond coding and design, game development encompasses many other audiovisual tasks. Character and environment design might suit an illustrator and may complement studies in clothing design or architecture. A closet composer could find a platform for their work through a hobby project composing game music. Keen writers can explore how they might combine their stories with the work of the illustrator using a tool such as Twine.

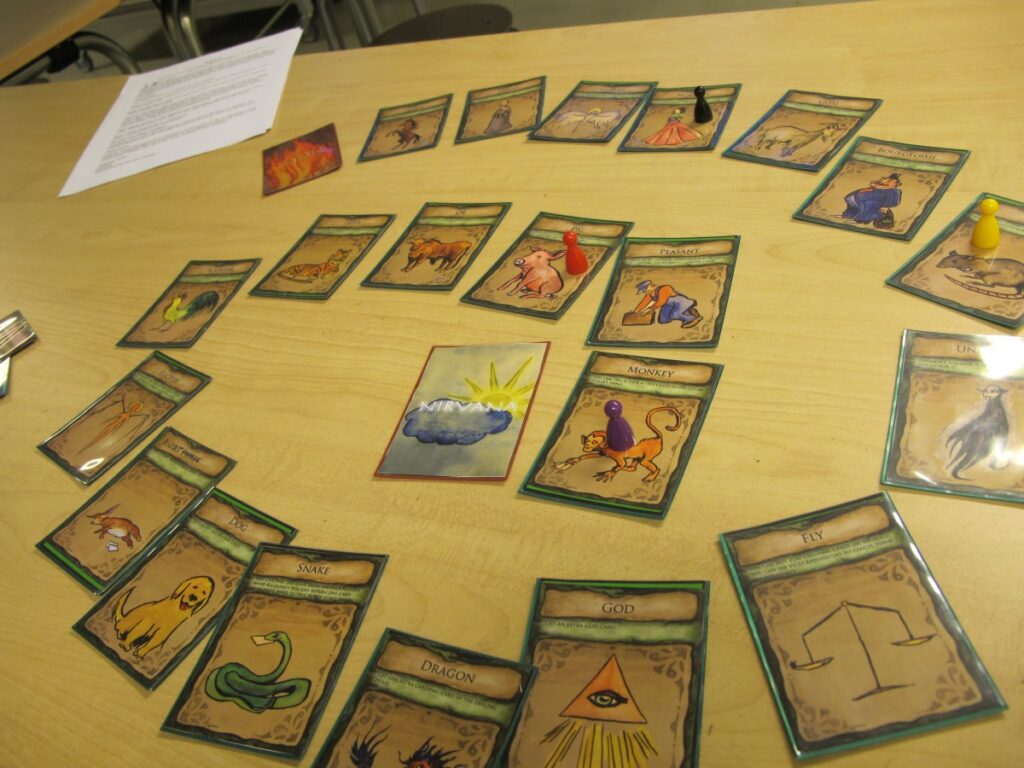

One form that creative gaming may take is roleplaying. Traditional tabletop roleplaying games see a small group of players gathered for hours around a large table, adventuring in a world modelled by the game master. Roleplaying is collaborative storytelling in which the game master describes the world and the situations the characters face. The players, for their part, describe what they would do in the situation to ensure the whole group succeeds in their quest. The outcome of battles and challenging situations is generally determined by the roll of a die and with the help of the rulebook.

Each participant in a roleplaying game can apply their creativity to solving problems and telling the story from the perspective of their own character. The greatest responsibility falls to the game master who must both keep the game world consistent and maintain the pace of the action. The game master can themselves devise the game world and adventures, even the whole game system, but most games make use of RPG books. As the Covid-19 pandemic has shown, tabletop roleplaying games can also be played remotely. Remote games work well over Teams, Zoom or Discord. There are also countless programmes you can use to ensure that maps, character sheets and dice rolls are assigned fairly. A good beginner-friendly roleplaying game system is Heikki Marjomaa’s Yhteiset Tarinat [Shared Stories]. The game has been successfully played remotely by first-time players in their 50s and 60s and would no doubt also work for younger players as an introduction the world of roleplaying games.

Finally and for starters…

For the generations who have grown up with digital gaming, games are as natural a mode of self-expression as, say, home videos or punk music may have been to previous generations. Success need not be the objective in making games. Your goal might be to have fun or address issues that are important to you or to network with your peers. There is a lot of interest in creating games, but parents and teachers familiar with more traditional forms of art may not necessarily know how to facilitate the hobby nor be able offer practical advice.

Ideally, individuals working with young people and within the cultural sector would have sufficient training in the secrets of game development to guide interested hobbyists towards appropriate tools and resources. Game industry professionals should also be encouraged to get involved in supporting and facilitating youth activities. This would not only help young people but would also benefit the sector as a whole: providing greater understanding of future generations, incorporating new creativity and ensuring the growth and quality of the workforce.

Author Jaakko Kemppainen, at the time of writing, works as Regional Artist for Games as Art at the Arts Promotion Centre Finland. He has earned his keep making, researching and supporting games for over 20 years. As a game designer, programmer and producer, he has been involved in the production of around 30 published games. His works on game design include Pelisuunnittelijan peruskirja [Basic Book for Game Designers] (2019) and 100 peli-ideaa [100 Game Ideas] (2022).