In 2022, a number of image generators became available to the general public. These applications enabled us to produce images of significantly higher quality than ever before with the help of various artificial intelligence techniques. By drawing a few horizontal lines across a computer screen, we were able to create a realistic landscape image; by feeding an AI system with a verbal prompt, we could create an artwork in the style of Van Gogh. In the media, there was particular interest in the copyright implications of AI art (cf. Räsänen 2022 and Virranniemi 2022) and speculation over whether the rights to the work belong with the individuals who come up with the prompt, the coders or the creators of the – perhaps thousands of – original images the AI system used to generate the image. The Tuu mukaan [Join in] project, developed by the Central Finland branch of Inclusion Finland KVTL Keski-Suomen Kehitysvammaisten Tuki, was particularly interested in the potential of AI-generated art to support self-expression and digital inclusion among young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The project set out to trial AI art creation in group programming for young people with additional support needs.

The AI art project grew out of the young people’s desire to organise their own art exhibition. The young participants were not too concerned about art techniques, as long as they would get to hold their own exhibition along with a proper opening night to celebrate, something the participants were already familiar with from earlier in the project. Creating AI images, however, was a completely new experience for the whole group. The young people were interested in AI-generated art but also a bit wary. Some were quite at home using technology and could navigate various digital communication channels with ease, while others struggled to use the equipment independently. In co-operation with the City of Jyväskylä digital youth work services, we settled on a trial in which the young people would have the opportunity to create art using AI system GauGAN 2, at cultural youth work centre Veturitallit. The young people were introduced to the program and equipment, and were also offered Augmented and Alternative Communication (AAC) interpreting and personal support and guidance as needed so that everyone would succeed in prompting AI and creating art.

There were some wonderful surprises, but we also encountered challenges during the process. Most of the participants found creating AI art surprisingly simple. The images were quick to generate and modify and it was easy to experiment with variations on the same subject. Creating the images using traditional methods would have been far more labour-intensive. Using the AI application enabled a whole new way of producing representational images for young people ordinarily only capable of abstract visual expression. The weird and funny details and errors in the images also provided a great deal of entertainment. The young people discovered that it is extremely difficult to get AI to deliver your vision accurately and the process always involves serendipity and surprises.

“It was nice to do the AI thing, and I got a good artwork” (participant)

“It was nice to make AI art and it was exciting to see the kind of artwork it turned out to be” (participant)

“It was nice to do art and the best bit was drawing on the computer” (participant)

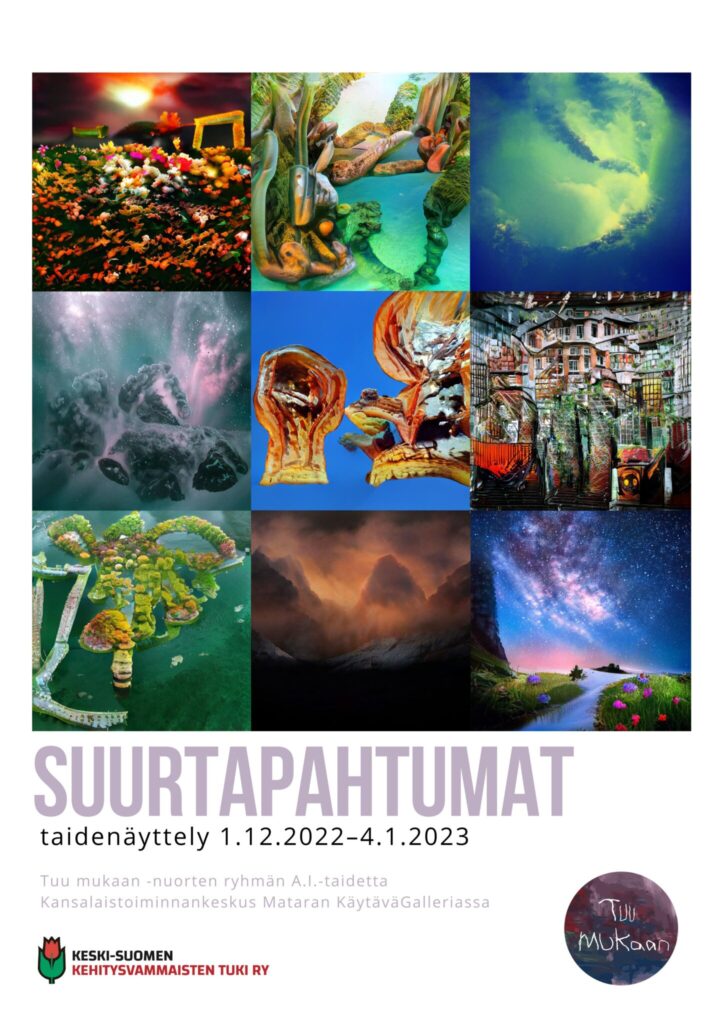

The young people’s collection of artworks ultimately became an art exhibition they named Suurtapahtumat (the Big Event). The exhibition was on display in Käytävä Galleria at the Civic Activity Centre Matara in December 2022 and January 2023. The opening, held as part of disability rights week celebrations, was spectacular, with live music and a buffet of treats.

Digital inclusion for young people with additional support needs

Using AI to create images is a relatively new approach and its full potential hasn’t yet been exploited in either youth work or in programming for those with intellectual disabilities. The young people’s exhibition received a great deal of attention and feedback, largely because these individuals with intellectual disabilities were among the first to experiment with AI as a group, to create a new culture around it and to share their output in the form of an exhibition. It was also meaningful for the young people themselves and this was evident in the pride with which they displayed their artworks and described their experiences with AI to guests at the opening.

This was something of a role-reversal. New technologies and digital culture generally reach those with intellectual disabilities more slowly than the general population, if at all. Accessibility requirements set out in the UN convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (The UN Association of Finland), the rights of persons with disabilities written into Finnish law (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, FINLEX 27/2016) and the Act on the Provision of Digital Services (FINLEX 306/2019) all steer society and the services system towards greater equality. In practice, these requirements – equality of opportunity and full inclusion and participation in a digitalising society – are insufficiently met, particularly for individuals with severe disabilities.

Digital inclusion, in short, is when an individual is able to utilize digital tools in a way that is meaningful and relevant and facilitates their daily life (Hänninen et al. 2021) For young people with intellectual disabilities, digital tools have the power to foster participation but also to limit young people’s agency where there is a lack of access to these technologies. Ensuring digital inclusion is a matter of equity; the use of mainstream technology has been shown to enable young people with disabilities to engage in activities without reference to their “otherness” (Kivistö 2019, 44). Digital participation has also been associated with an improvement in the life chances of young people with disabilities, particularly those living outside the capital area, where opportunities to engage with different communities may otherwise be extremely limited (Eriksson 2019, 4). If, however, barriers are not removed and appropriate support not put in place, our increasingly digital society will leave some young people behind. Supporting the digital inclusion and agency of young people with intellectual disabilities goes beyond assistive technology or technological solutions. It is important we empower young people with disabilities through their skills and abilities and through the support of those around them (Kivistö, M. 2019, 44–45).

Digital participation as a means to cultural inclusion

Kaarakainen (2022) notes that digital inequality and digital exclusion prevent individuals engaging in the normal relationships, activities and programmes that are accessible for most people. Those at risk of digital exclusion include young people with cognitive impairments, such as language and learning difficulties (Kaarakainen 2002). Young people with intellectual disabilities are particularly affected. It is also worth noting that – despite the different everyday challenges they face, and additional support needs they may have – these young people’s needs and aspirations for a meaningful life and leisure time do not differ significantly from those of other young people of the same age (cf. Eriksson 2019, 23). What they want and need when it comes to digital participation is also similar. Those working with young people must provide opportunities to engage in a range of digital activities as well as offering support and guidance to those who need it most.

Supporting the digital inclusion of young people can be seen in the context of mechanisms for promoting inclusion more broadly (cf. THL 2022). When our default is barrier-free access to (digital) environments with genuine opportunities for everyone to participate – through economically- and socially-accessible leisure activities and peer interaction –, this also supports the digital inclusion of disadvantaged youth. The key is to offer young people the right level of support, to offer support that reflects their needs, and to offer this support in such a way that they retain their autonomy. It is also important to acknowledge that young people with severe disabilities may require ongoing support and guidance to enable them to use digital platforms and autonomy may only be possible with the assistance of others. Even when an individual is reliant on the assistance of others to participate, the experience of participation is still personally meaningful.

“It was nice to come up with a name for my own artworks and it was nice when they were on display at the exhibition” (participant)

“The best part was that the show became something unique” (participant)

While digitality has no intrinsic value, it is one pathway to participation and to feeling included. Kaarakainen (2022) notes that the broadest positive impacts are found in digital interventions that centre individuals’ personal lives and social interactions. Meaning comes from interaction with others and from taking the things that are already important to people and delivering them digitally. This was also one of the foundations of the Tuu mukaan youth AI art project. The young people’s ambition was to hold their own art exhibition, and this was accomplished with the use of digital tools that provided them with the opportunity to express themselves in a whole new way. The art exhibition was, nevertheless, a real, physical event where people could engage with others in person. These young people may have learned something about artificial intelligence and got the hang of using digital tools, but above all, they had an opportunity to feel part of the digital culture of our time. They were credited as artistic creators, who – if they fancied – were more than capable of putting on a Big Event!

Tips for co-ordinating similar projects:

- Check out the various AI image generators in advance (e.g. StableDiffusion, Dall-E , MidJourney, nVidia Canvas etc.) The group can also experiment with these and chose one themselves, if there’s enough time.

- Be aware that some image generators require an email address to sign in. It’s good to let participants know this in advance so that everyone comes prepared with all the information they need to sign in and you can get straight to work.

- Consider the support needs of your participants and ensure there is appropriate guidance available. Participants can also benefit from planning and sketching out their designs on paper before getting started on the computer.

- The images produced by image generators tend to be rather low resolution. Small images are fine when printed, but larger ones can look blurry. There are dedicated AI applications – image upscalers – you can use to increase the size of the images.

- Sharing art is part of the process. Traditional exhibitions, online exhibitions and group discussions can all promote interaction around the work.

Author Maiju Räsänen is Tuu mukaan Project Co-ordinator at Keski-Suomen Kehitysvammaisten Tuki.

SOURCES

Eriksson, S. 2019. Vammaisten asema, vaikuttaminen ja digitaalisuus. Invalidiliiton julkaisuja R.29.

FINLEX 306/2019. Laki digitaalisten palvelujen tarjoamisesta

Finlex 27/2016. Yleissopimus vammaisten henkilöiden oikeuksista

Hänninen, R., Karhinen, J., Korpela, V., Pajula, L., Pihlajamaa, O., Merisalo, M., Kuusisto, O., Taipale, S., Kääriäinen, J. & Wilska, T-A. Digiosallisuuden käsite ja keskeiset osa-alueet. Digiosallisuus Suomessa -hankkeen väliraportti. Valtioneuvoston tutkimus- ja selvitystoimikunnan julkaisusarja 2021:25.

Kaarakainen, M-T. 2022. Digitaalisen syrjäytymisen ehkäisy osaksi nuorten kohtaamista. Verken blogi 21.3.2022.

Kivistö, M. 2019. Vammaisten nuorten teknologisten toimijuuksien rakentuminen digitalisoituvassa yhteiskunnassa. Katsaus laadulliseen tutkimukseen. Nuorisotutkimus 35 (2017):4.

Räsänen, P. 2022. Greg Rutkowski ei löydä pian enää töitään tekoälyn väärentämien joukosta: Internetin rakastamat ohjelmat ovat ongelmallisia. Helsingin Sanomat 12.11.2022.

Suomen YK-liitto. 2015. YK:n yleissopimus vammaisten henkilöiden oikeuksista ja sopimuksen valinnainen pöytäkirja.

Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos 2022. Osallisuus.

Virranniemi, G. 2022. Lensa AI villitsee somessa, mutta varastaako tekoäly taiteilijoilta? Graafikko, kuvataiteilija ja valokuvaaja kertovat, mitä ajattelevat. Yle 23.12.2022.